On Friday, January 3, police officers attempted to arrest suspended South Korean president Yoon Suk Yeol. The police entered the grounds of the president’s residence where they were met by armed soldiers loyal to President Suk Yeol. The two groups clashed. The BBC reports (Mackenzie, 2025):

As dawn broke, the first officers ran up to the house, but were instantly thwarted – blocked by a wall of soldiers protecting the compound. Reinforcements came, but could not help. The doors to Yoon’s house stayed tightly sealed, his security team refusing the police officers entry.

For several hours the investigators waited – until, after a series of scuffles between the police and security officials, they decided their mission was futile, and gave up.

This is a moment of decision.

What is Power?

Power is the capacity to nullify, to negate, to arrest, to control the enemy. The enemy’s beliefs and convictions don’t enter into the picture in the exercise of power. The enemy is a subject. He is simply nullified. His will and desires mean nothing.

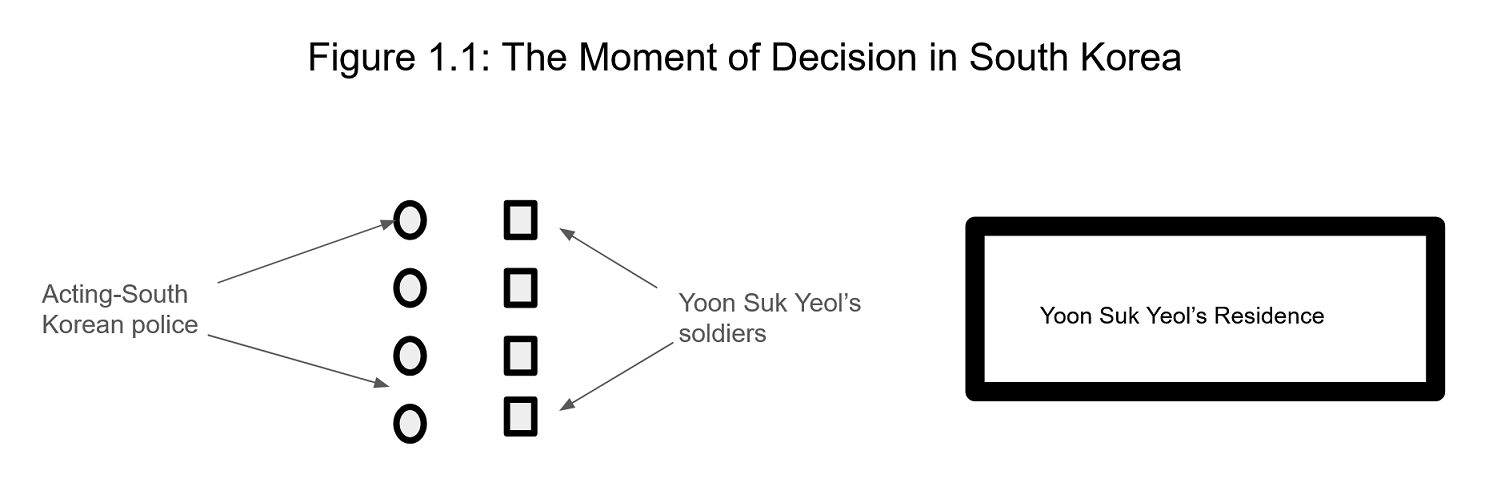

In the case of Yoon Suk Yeol, we see a clear case of power-conflict exemplified in a moment of decision. A moment of decision is when one actor attempts to nullify another. In the case of South Korea, one group of actors, in this example government officials personified in the new acting President Choi Sang-mok, attempted to nullify former president Suk Yeol. Figure 1.1 provides an abstract representation of the moment of decision.

The attempt began weeks ago. First, Yoon Suk Yeol was impeached. Next, a Seoul court commanded Suk Yeol to attend questioning sessions which Suk Yeol simply did not attend. Afterwards, the same court issued an arrest warrant for Suk Yeol. The former president ignored the arrest warrant. Finally, police officers were sent to Suk Yeol’s personal residence and attempted to arrest the former president. More than 200 soldiers physically confronted the police officers and physically resisted them; some of the soldiers were armed (Ewe and Kwon, 2025). Consequently, President Suk Yeol was not arrested; he was not nullified. As a result of this moment of decision, we can say both President Suk Yeol and acting South Korean President Choi Sang-Mok have power: they both have the capacity to nullify enemies. A true test of President Suk Yeol’s power would be if he could dispatch soldiers to detain President Choi Sang-Mok and maintain the detention. If Suk Yeol could detain Sang-Mok and continuously maintain Sang-Mok’s incarceration, then Suk Yeol would ipso facto be the more powerful actor in the case of South Korea. Regardless of the outcome, the action of dispatching units which obey two separate authorities demonstrates that two power-groupings exist in South Korea.

This moment-of-decision situation illustrates the potential for civil conflict in South Korea, a situation that will be resolved in one of three ways. First, Choi Sang-Mok and the government he represents may yield and allow Suk Yeol to continue to ignore their concrete authority. Second, Suk Yeol may submit to the new governing authorities and allow himself to be arrested. Third, the two sides may attempt to nullify the other, leading to civil conflict with the potential for both civil unrest, and, ultimately, civil war.

Regardless of what happens, the case of Suk Yeol in Korea, along with numerous other case studies such as the decades-long drug war in Mexico, demonstrates two things. First, these case studies show the difference between influence and power. The acting government of South Korea obviously has influence. Choi Sang-Mok’s government can issue commands to police officers and policemen willingly attempt to carry out the order. However, the governmental police are unable to carry out an arrest warrant, because they lack the physical capacity to nullify Suk Yeol when he resists them. In consequence, we can say that the acting government of South Korea is influential but weak in terms of power. The same can be said of the Mexican government when it attempts and fails to arrest the leader of a drug cartel.

Second, the conflict between Suk Yeol and the acting South Korean government exemplifies the moment of decision. By moment of decision I mean when power is attempted to be utilized. In the case of Suk Yeol, the moment of decision came when governmental police attempted to arrest Suk Yeol. It doesn’t matter if the attempt fails or is successful. Regardless of the outcome, any arrest attempt is a moment of decision: an attempt to nullify an enemy.

Some observers seemed stunned by events in South Korea, as if they were somehow novel or unique. Consider Mackenzie (2025):

This is totally uncharted territory for South Korea. It is the first time a sitting president has ever faced arrest, so there is no rule book to follow – but the current situation is nonetheless astonishing.

When Yoon was impeached three weeks ago, he was supposedly stripped of his power. So to have law enforcement officers trying to carry out an arrest – which they have a legal warrant for – only to be blocked by Yoon’s security team raises serious and uncomfortable questions about who is in charge here.

The truth is the concrete power situation developing in South Korea is the same as the concrete situation which has existed in Mexico for decades: two powerful actors existing in the same physical space who are unable to nullify one another. This is the moment of decision, a sociological phenomenon that is endemic to human affairs for our entire history. Put succinctly: there is nothing new or novel taking place in South Korea. It is only a moment of decision.

References:

Ewe, K. & Kwon, J. (2025). Who is Yoon Suk Yeol, South Korea’s scandal-hit president? BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cx2nyp3pxrko

Mackenzie, J. (2025). A dawn stand-off, a human wall and a failed arrest: South Korea enters uncharted territory. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cp8n0ng2m88o