By: Luke Wolf

Editor’s note: In the series Lost Art, Luke Wolf explores important artistic works that have garnered little attention in the English-speaking world.

The human heart is a locomotive, choosing to go or stop; but the path is dictated by the rails, by what is possible. As it is written: man’s heart deviseth his way, but the Lord directeth his steps (Tarulla).

Erotic love. Total obsession. There are few works that capture its essence. One of them is the unique film Chilly Scenes of Winter (1979).

In Chilly Scenes of Winter, Charles, played by John Heard, the father of Kevin in the film Home Alone, falls desperately in love with a coworker he should have never met. Charles is a mid-level bureaucrat who spends his work days listening to music and surreptitiously drinking while playfully flirting with the numerous women in his office. The film is delightfully honest about the uselessness of many government workers, jovially poking fun at the absurdity of government work. Then, one day, a coworker is sick and Charles is forced to deliver his reports to a receptionist three floors away. The two have worked in the same building for years and never seen each other.

There is a knowing look that “star-crossed” lovers experience, a look of total adoration rendered in a split second, fast as fire touching gasoline – something involuntary, which can’t be hidden. It’s a tangible force. That’s the look, based on the unique human attribute of irrational eroticism, Charles gives Laura, the receptionist who takes his reports. From the first moment he sees Laura, Charles can barely think. She literally takes his breath away (Figure 1.1).

This is the decisive mechanical moment of erotic love. Charles hasn’t spoken to Laura before. He’s never seen her before and yet he’s instantaneously totally enamored with her. An ineffable, irrational mechanism is working on Charles, triggering an obsession that he can’t help, and often wishes he never experienced. A similar moment is captured in the film Excalibur (1981) when Lancelot first sees Guinevere – all she is doing is walking down a set of stairs, rather foolishly, and erotic love bodily slaps Lancelot like a hammer (Figure 1.2). A related scene occurs in Damage (1992), when Jeremy Iron’s character first witnesses his love obsession (Figure 1.3). One is reminded of Goethe’s Werther, who falls madly in love with Lotte after exchanging approximately eight sentences to her. The same is true of other iconic characters: Romeo, for example. Then there is King David, the man after God’s own heart, who obsessively-lusted for Bathsheba and had never spoken to her. The King had merely seen her from across a street. The whole phenomenon reminds a man of Dante, who saw his beloved Beatrice about twice in his entire life. This is how he described worship-peering at Beatrice:

I determined to stand in company at the service of a group of formally-attired ladies. Then I seemed to feel a wonderful tremor begin in my breast on the left side, and extend suddenly through all the parts of my body. Then I say that, dissembling, I leaned against a painting which ran around the wall of this house, and fearing lest my trembling should be observed by others, I lifted mine eyes, and, looking at the ladies, saw among them the most gentle Beatrice.

Chilly Scenes of Winter deftly captures the “wonderful tremor” Dante spoke of – and the obsession that almost inevitably follows.

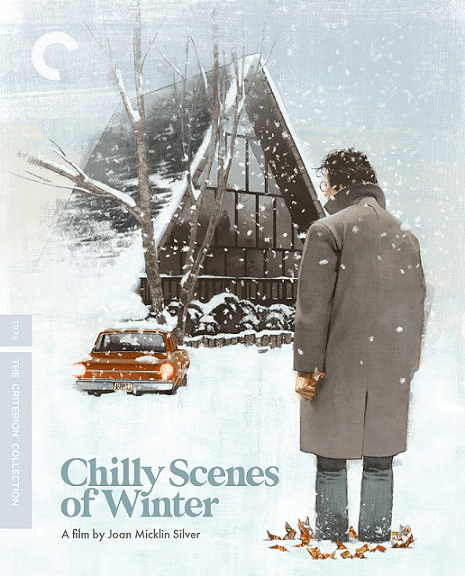

Marred by an annoying subplot involving Charles’s mother, the main plot traces the tragic relationship between Charles and Laura. Using an interesting, non-linear story method, the director, Joan Micklin Silver, traces the spiral of obsession Charles experiences for Laura. He imagines her when she’s not there – having entire conversations with his desideratum-projection. Here is a man who sees his love in walls, wills her image into existence in the seat next to him, a man that longs for a woman the way high-divers gulp cold oxygen when they bust the liquid surface of the pool. At random moments, Charles just stops what he is doing and stares into the middle distance – compulsively thinking of Laura. He parks his car across the road from her house and watches the distinctive A-frame home, projecting a cult-like spirituality on the building because it houses his love, the way medieval Christians revered relics. Our loves spiritualize material existence, transforming the inconsequential into something almost holy. That’s why Tarulla says erotic sex is the closest the common man comes to transcending the physical world. In eroticism, man is beyond rationality, and wholly given over to the rapid-frothing river taking him whichever way it flows. Put succinctly, Charles’s obsession over Laura is one of the truest portrayals of erotic love ever put to film.

A pensive study of an irrational compulsion in the midst of a highly-rational modern city, Chilly Scenes of Winter operates in the firm tradition of passionate eroticism that is such a distinctive element of Western Civilization. Charles’s love of Laura is beyond sex but sex is part of it. It’s a film for serious people, all five of you. Do yourselves a favor and spend the evening with Charles and Laura. You won’t regret it.

Chilly Scenes of Winter is available free of charge for a short time at the link below.