Aymeric Chauprade (Professor of Geopolitics; Collège Interarmées de Défense)

Translated by Luke Wolf

How can we define Geopolitics?

The study of political relations between states, intra-state movements such as rebellions and trans-state powers such as criminal networks and multinational corporations is based on geographic criteria, the study of geopolitics highlights the importance of geographical criteria – physical, identity, resources – which sheds invaluable light on the political relations between states and non-state actors. For geopolitical thinkers such as the historian Jean-Baptist Duroselle, physical geography, identity and resources are profound forces of history.

One of the characteristics of the new French school of geopolitics, inaugurated by the work of François Thual in the early 1990s and continued by my own, is to reject any ideologization of history, any reduction to a single cause, and to emphasize the importance of identity factors in conflicts between political societies. This school of international relations can be described as neo-realist, and is in stark contrast with ideas of international relations propagated from the United States. The French geopolitical school believes that states remain major players in international relations, that they develop interests, partly explainable by the realities of geography—physical, identity-based, and resource-based. Of course, the role of ideology is important. Ideology complements geography and interacts with it.

Physical Geography – Location is Key

The first consideration in geopolitical analysis is physical geography. Two geographical situations must be distinguished because they determine different behaviors in foreign policy: insularity and landlockedness. Indeed, in many conflicts, the will of an island’s population, for example, to separate from an overarching political entity—separatism in Indonesia—or to form a single state—Ireland or Cyprus—is the deciding factor. In many other conflicts, it is the desire to open up to a sea or ocean that causes tensions between neighboring states. The sea brings trade. The sea brings invaluable infrastructure. The sea brings access. Technological progress has, in some respects, made it possible to mitigate the constraints of geographical location. However, it has not freed actors from their position on the map. And the behavior of states, as well as that of intra-state actors—rebel movements within states—remains primarily determined by this position.

The second criterion of physical geography, after an actor’s position on the map, is the geographical environment. Landscape and climate are key factors in political dynamics in many parts of the world. The fact that the Kosovo region is mountainous led the Americans to prioritize massive bombing of Serbia to avoid a ground engagement. The situation in Iraq is very different: the enormous American war machine could easily deploy across the Iraqi plain, from the shores of the Gulf to the capital Baghdad. This terrain is ideal for a modern army, until it encounters the city, a modern form of landscape conducive to deadly guerrilla warfare.

The Physical Location of Identity and Resources

After physical space comes people. Geopolitics takes into account the geography of identities, that is, both the presence of people in the territory and the characteristic features of these human communities, what differentiates them, what sets them apart. Geopoliticians often note the non-coincidence of state borders and identity borders. The map of states does not exactly overlap that of peoples—ethnicities or nations. This results in identity claims, which in turn lead to conflicts. In the contemporary world, as in the past, many identity communities are questioning their state of belonging; many states are shaken by separatist demands and internal tensions between different ethnic communities. This phenomenon can be observed from Sub-Saharan Africa to Central Asia, including the Caucasus and Southeast Asia, and even regionalist issues in Western and Central Europe. Identity tensions are not limited to ethnicity; they are also religious. When mapped out, the key religions of the world do not coincide with the map of states and people. When scholars refer to the “map of civilizations,” we often mean a map of religions because religions are often the wellspring of culture – they are the seed from which grows the tree of communities.

Many conflicts today stem from the mismatch between these three maps: the map of states, the map of ethnic identities, and the map of religions. Identities shift throughout history. The demographic variable that geopolitics takes into account expresses this historical movement. To engage in geopolitics while ignoring demographics would present a false, static, fixed vision of history, precisely when we need to have a dynamic vision and understand the movement of history. The fact that Russia’s population density is ten times lower than China’s immediately indicates the direction in which future population flows will go. Russia will increasingly fear China. And now, to the maps of states, peoples, and religions, we must add another: that of resources, from water to oil, including gold and diamonds. Now, to the maps of concrete existence, of politics, and of identity, we must add the map of possession, the map of the covetousness of resources.

The Geopolitical Method: Systemic Approach

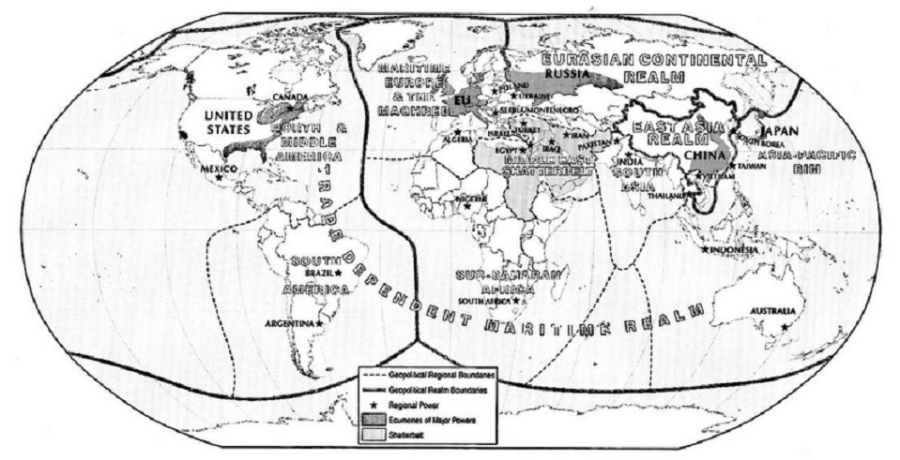

Each geopolitical situation must be approached by taking into account all of these geographical factors: physical, identity, and resources. Each situation is modeled as a kind of system of forces. This is what we call a “systemic approach.” Let’s take an example. We want to understand the geopolitics of a given regional area. We must begin by identifying the power players: states, intrastate movements, the presence or absence of transstate powers—networks—and indicate which ones can be considered centers of power—everything is centers around them—and which can be considered peripheral—the periphery receives and are subject (the perfect word!) to the power of the centers. Russia, for example, is a center of power, while the Central Asian republics, the Caucasus countries, and the Baltic states will be considered Russia’s periphery of power.

Once the central and peripheral logics have been identified, geopoliticians consider the importance of the geographical situation. Are we dealing with the logic of islands or the logic of opening up a separated area (landlocked, for example)? Then comes the importance of terrain. Are there, for example, difficult terrains—mountainous areas, scrubland, marshes, impenetrable forests—that are inherently favorable to the maintenance of armed rebel movements? We then draw up a map of identities, which we compare with the map of states. Potential separatism or irredentism—the desire to join another state—are then illuminated. Demographics indicate in which directions the dynamics will develop; will they diminish or intensify? Are resources at stake—oil, for example— can these resources support a rival power actor?

Geopolitics, Ideology, and Power

Finally, geopolitics must enrich our understanding by its analysis. It does this by taking into account non-geographic power factors that nonetheless play a crucial role. Let’s imagine that, in the regional area under study, there is a state possessing nuclear weapons. Nuclear power, a non-geographic factor in essence, partly determines the relationship between this state and its neighbors—and actors beyond its neighbors. There is therefore, in geopolitics, a real spirit of method. Each situation mobilizes a multiplicity of geopolitical factors to which are added numerous non-geopolitical factors. The explanation therefore cannot be caused by a singularity explanation—with a single cause. Just as history cannot be reduced to a “class struggle,” it cannot be reduced to a struggle between “races”—peoples and ethnicities—a clash of civilizations—religions—or even a war of fire—oil. All these simplifications and reductions of history to a single cause, so easily filtered through the media, are contrary to the spirit of geopolitics. This does not mean, however, that things are so complex that they cannot be explained. The truth can indeed be approached through the most comprehensive modeling possible.

Geopolitics is a science based in concrete reality. It is not immune to exploitation by authoritarian politicians. Geopolitics has a history, sometimes a controversial history. The German geopolitical tradition was the true brain of Pan-Germanism, with the terrible consequences this entailed for Europe.

As for English and American geopolitics, it has constantly envisioned the world empire. France’s policy of balance knows something about this type of thought.

But fundamentally, geopolitics is no more exploited than sociology or economics are exploited today. The important thing, moreover, is that geopolitics is a genuine scientific discipline, on a par with geography or history. What’s also important is that it has experienced unprecedented growth in France over the past ten years, even if the word’s popularity has led to its misuse by journalists and researchers. Its success, in any case, is inversely proportional to the weight of these reductive ideologies that have caused so much harm to Western universities since the French Liberation from Nazi Germany and that have alienated generations of students from concrete reality.